Ageing comes with a reconfiguration of relationships. With each birth, with each death, a relationship oscillates until it finds its new equilibrium. Our siblings are perhaps the people who can closest bear witness and attest to these changes in our lives. So many shared experiences, yet such uniquely different interpretations of them.

The final season of Succession reflected this restructuring of relationships. ‘Connor’s Wedding’, with the death of the colossus, the tyrant Logan Roy, and the visceral reaction it wrenches from the three Roy siblings brought forth tears. Episode Nine, ‘Church and State’, and the gloriously grand Catholic funeral was the perfect setting for emotional turmoil and even further tears. In part because they’re all brilliant actors (future EGOT winner Jeremy Strong prayer circle). But also, because it brought to mind my grandfather’s death in Pakistan last year.

What was originally planned to be a two week jaunt turned into an emotional upheaval. The days I remember strongest are the immediate aftermath of the funeral. No mourners. Only a house echoing with the loss of its central figurehead, whilst my mother and her brothers plan for what comes next, planning their own succession of sorts.

It’s rare to ever consider our parents as fully realised human beings. However, in that week I saw more of my siblings in watching my mother and two uncles, then I might ever have. The petty squabbles, raucous laughter and undercurrent of unbearable grief. It was a reminder they lived full, varied lives before we knew them.

Succession is interesting in that the three adult Roy siblings’ lives (Connor forgotten, but not gone) very much rotate around their father. Their identity carved by their connection and proximity to him. “My God, I hope it’s in me”. Kendall may have kids, may have a family. But first and foremost, he will always be known as Logan’s son (my favourite tiktok when I was delulu and thought Kendall would win). Their unmooring and reconfiguration with his death reflected what I witnessed with my own mother and uncles. It cast a new light on their grief.

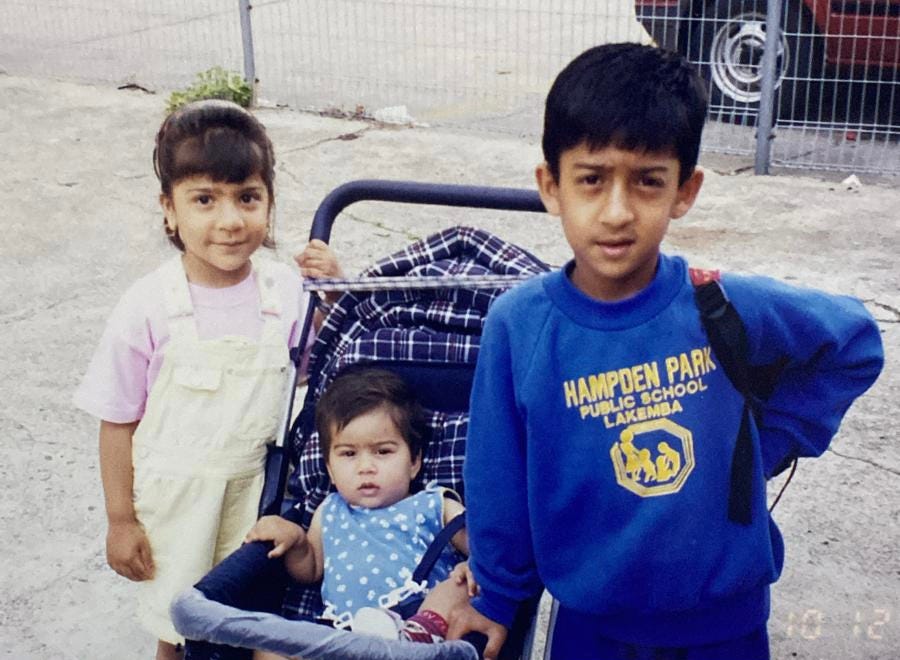

I’m told my brother cried when I was born. One younger sister was already enough. Two was too much.

I’m told my sister cried, trying to console me as a baby, singing ‘happy birthday’ through her tears, alone at home.

Fights. Tears. Laughter. Grim concepts like death didn’t exist in our childhood.

My sister got married many moons back. But I still remember her wedding day. More so because I wasn’t there. But really, more so, because despite my overwhelming happiness for her, there was also conversely a selfish sense of loss. Suddenly the final death knell of childhood had rung. There would no longer be nights where I stormed her room to perform a disastrously choreographed dance to Florence and the Machine. Or dinners where my brother and I drove her to tears, picking on her in the remarkably cruel fashion that only siblings can.

It’s so easy to yearn for the nostalgia of the past. To wish for a time where things were simpler, either simply because they were, or they appeared so. But growing up is having to contend with these difficulties. It’s that reconfiguration of relationships; learning when to let go or hold on.

It may no longer be just us three, but in some ways, it will still always be just us three.